A Review of Sophie Mars’ Mirror Me

Between the Virtual and the Physical:

A Review of Sophie Mars’ VR Experience Mirror Me

Mirror Me is an immersive Virtual Reality (VR) experience by Berlin-based artist and dance therapist Sophie Mars. This experience was first exhibited at Exposed Arts Projects, London, in February 2022. The Ainalaiyn Space curatorial team was kindly invited to experience Mirror Me. Now, curatorial assistant Phoebe Bradley-White reflects on her experience.

By Phoebe Bradley-White, 22 July 2022

Sophie Mars, Mirror Me, 2021. Photography by Sophie Le Roux.

Knocking on the door of Exposed Arts Projects, I was greeted and invited inside by the artist in the guise of their alternative being, a nameless nonhuman presence who guides the participants between the physical and the digital. Every part of their body was covered by a cream-coloured material, except for their eyes. Mars designed the guide’s outfit to be intentionally neutral, in order to shift attention from the body’s appearance to its presence. Their presence felt calming yet highly attuned, as though they were intuitively responding to my mood.

The guide invited me to participate in a series of embodiment practices in a small room above the VR space. Sitting down, I first noticed the scent of eucalyptus or mint. I closed my eyes and was lead through a series of breathing exercises and body scans which intended to relax, ground and clarify each participant before exploring Mirror Me.

Returning to the room downstairs, the guide assisted me in putting on the VR equipment. Again, the room lingered with the fresh scent of eucalyptus. I was dressed in equipment strapped around my chest and feet; I was given one controller for each hand; and a headset was placed over my eyes. Whilst wearing the headset, my primary senses began to shift. I became aware of how cold and hard the floor felt against the soles of my feet. I could hear the gentle buzzing of electricity from the lightbulbs. Although I could not see my guide, I could sense their presence close by.

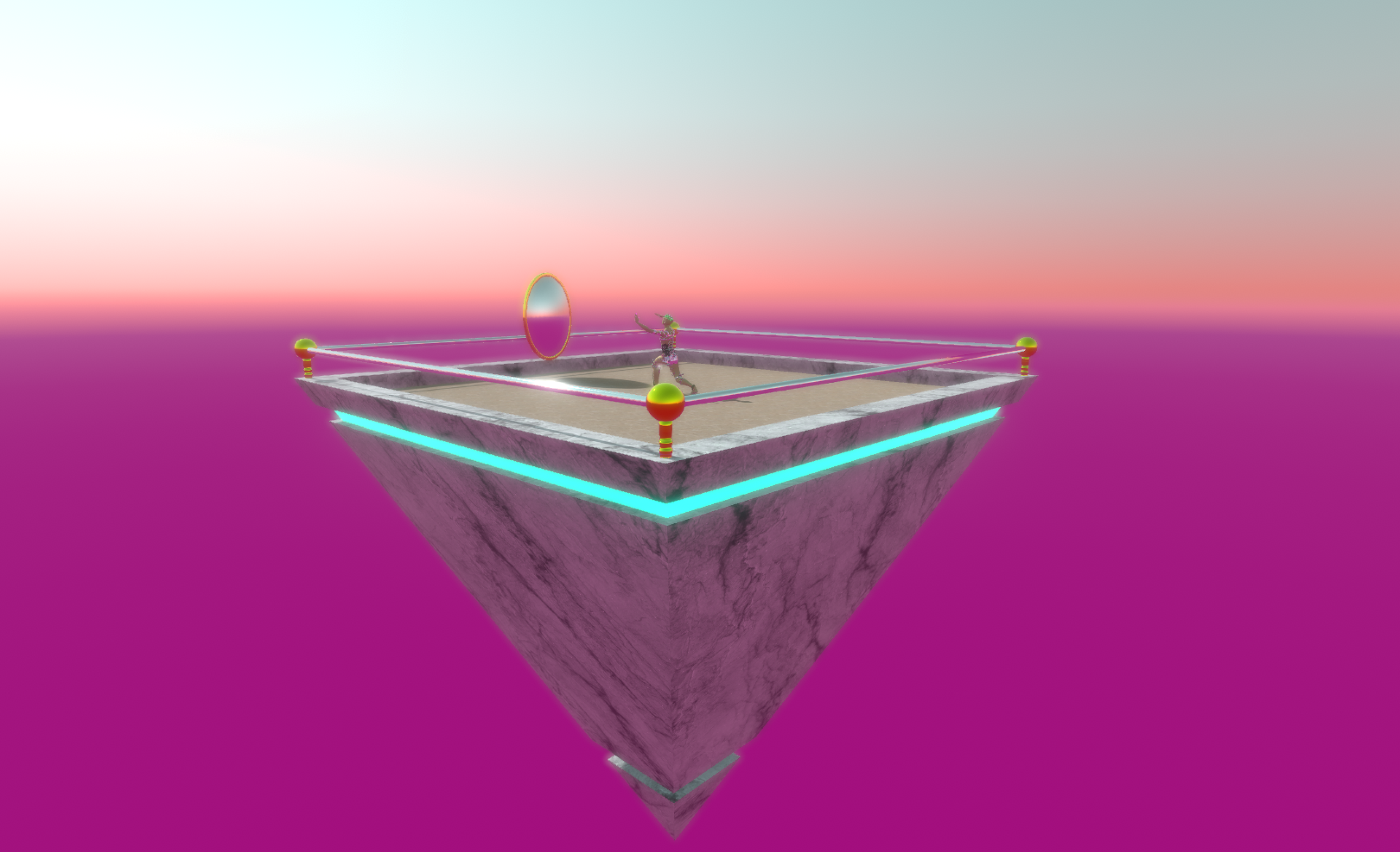

At first, there was total darkness. Floating, I was soon gently pulled into a white light. A deep pink emerged, warming to an orange before becoming a pale pinkish-blue. An orb of light, perhaps a sun, shone down from above, recalling a surreal and endless horizon line. Looking at the ground, I noticed that I was stood on the square base of an upturned triangular prism. What was once the portal-like body of light had now become an oval mirror that hovered before me. In this surreal landscape and gazing into the mirror, I was confronted with a virtual being. Was I this being or were they simply mirroring my movements?

Sophie Mars, Mirror Me, 2021. Photography by Sophie Le Roux.

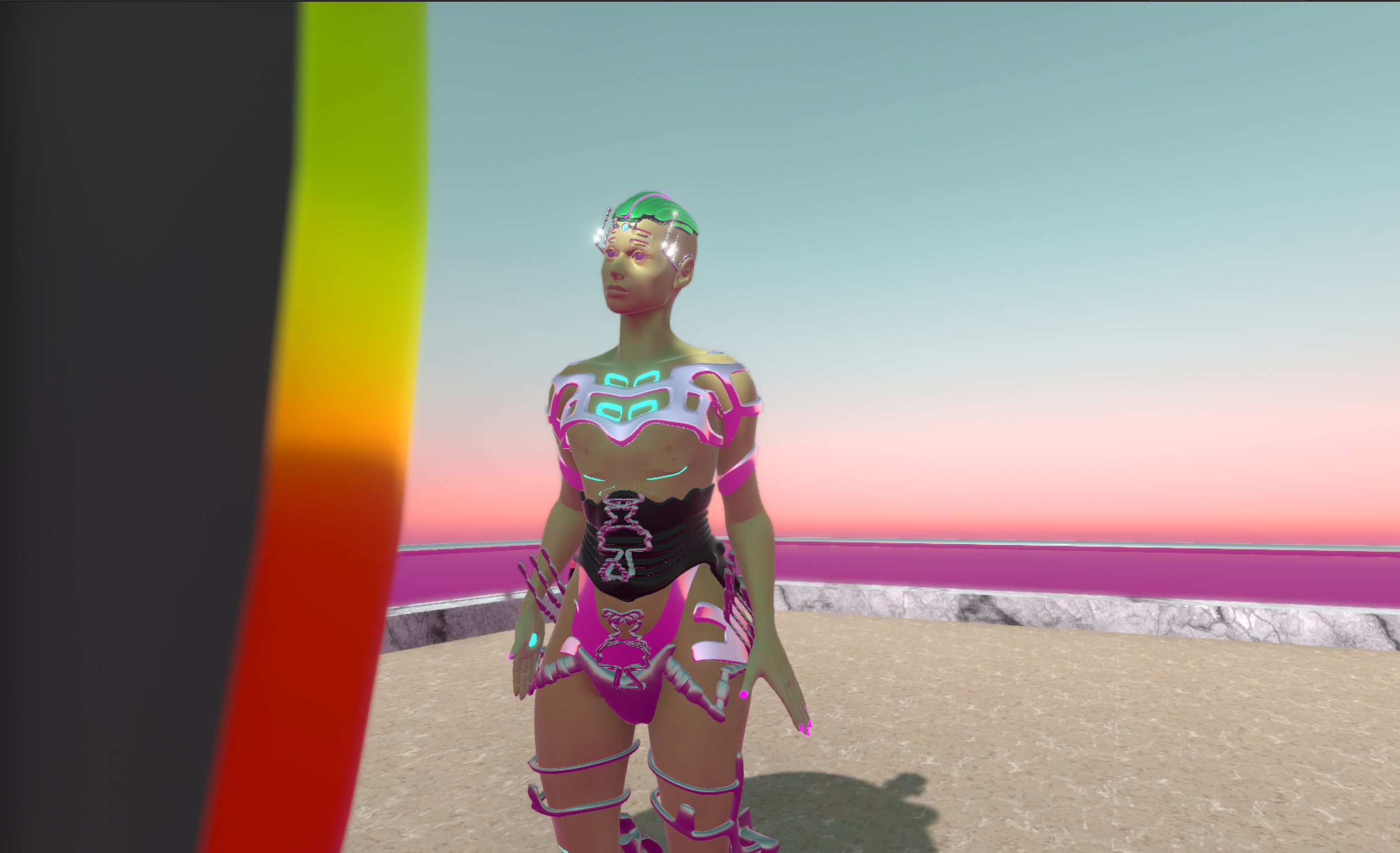

While this being had pink abstract bodily adornments and painted nails, their body was not obviously sexed or gendered. A constant radiation of green-blue neon radiated from small lines and holes within the being’s torso, bald head and palms, as though emanating from within. Glancing down at myself, I realised that I inhabited the same body, making the being before me my reflected image.

As someone with limited experience of VR technology, I was amazed by the world I saw around me, but while I was completely consumed by the surreal virtual landscape, I felt simultaneously aware of the physical world. The guide encouraged me to move about the space and to explore the movements of my own and my mirrored body, yet I found myself hyper-sensitized to the world I thought I had just left behind. I wondered if sudden movements would cause me to slip, or if I would accidentally knock the guide or collide with the furniture. Exploring the in-between of the physical and digital worlds, I had never felt more aware of my body and its relationship to its surroundings. I thought VR would enable me to escape the physical world, but I began to feel intensely rooted within it instead.

Betwixt virtual and physical realities, my sense of proprioception intensified. At first, I moved slowly; raising one arm and twisting my wrist, I examined the pin-prick pools of light emanating from the palms of my hand for several minutes. I moved at such an incremental pace that, when I kneeled down, I could feel each vertebra in my spine shift as my back arched. I finally noticed how heavy and tired my feet felt, a sensation I increasingly neglect with each day living in central London.

Mars began developing Mirror Me several years ago, as a practice that would enable the artist and participant to experience different bodies and embodied sensations. While the VR experience is rooted in the body and in relishing in the reality of the present moment, its visuals present the participant with an imagined being and extrasensory experiences that innovatively synthesise technology and the body.

In our contemporary moment, there is a division between the digital and the embodied. In a recent discussion with the artist, Mars highlighted the practices of turning off one’s phone and exploring nature or ‘doom scrolling’ on one’s phone, to numb and distract, as prime examples of the way the body and technology are perceived as mutually exclusive. (1) Yet, Mirror Me asks its audience to think about the symbiotic relationship between the senses and sensations of the body and technology. While the artist agrees with the importance of taking time away from phones, the internet, social media etc., her practice facilitates a thoughtful dialogue between the human and the technological.

Sophie Mars, Mirror Me, 2021. Photography by Sophie Le Roux.

With training in dance therapy, Mars and this most recent project showcase how technology and the body can be explored simultaneously as transformative tools. When used mindfully and creatively, technology can facilitate the expansion of our embodied experience; it can be playful, surprising, grounding and can perhaps even foster empathy. If, as the artist explains, two people can foster mutual empathy by moving together, then Mirror Me allows the participant to dance with themselves. (2) To move with our virtual selves, a digital body in complete alignment with the rhythms of our physical body, can enhance our self-compassion and empathy.

This potential to direct empathy and compassion towards ourselves offers radical and liberating implications. Mirror Me offers a unique opportunity to explore oneself through presence, rhythm and movement. No longer seeing their body through the lens of social conditioning and self-critique, the participant can experience their body instead of simply perceiving it, offering a relationship with the mirror and self that feels tender, welcoming and honest. In a world where we often numb, ignore and neglect, this experience was refreshing and healing; psychic bruises and physical dissociation felt soothed and remedied.

Returning to the experience of Mirror Me, the guide suggested I press a button on the handset to explore creating an aura. Following their instruction, a marbling ice blue formed an orb around me; looking into the mirror, I could see the mirrored being was also being encased in this light-form. When I released the button, the colour slowly dissipated, leaving me exposed to the burning white sun above. If I held the button, the blue form would eventually become fully opaque. While I had no sense of time in this virtual reality, I developed a sense of duration. I could not sense what time it was, but I could feel time moving, or more specifically, I could feel myself moving within time.

Prompted by the guide, I pressed another button on the handset and began to elevate from the ground. I left my body behind, now able to see the mirror being in both the mirror and where I was once stood. For me, this sensation was the most fascinating, and I spent much of my time within the performance experimenting with my own rising and falling. Mars was watching my movements on a monitor in the room the entire time, observing what movements and sensations I was most drawn to. “Art should always be an experiment”, the artist stated in one of our discussions, and this experience was created not only for the participant to experiment with new sensations, but for Mars to understand the sensations participants felt most drawn to. (3) With our movement restricted, our bodies feeling more fragile than ever, and our bodies affected by the stress of unprecedented times in the past few years, perhaps Mars was collecting information on how her next projects could best heal us. Therefore, Mirror Me is both a pertinent and poignant project.

Sophie Mars, Mirror Me, 2021. Photography by Sophie Le Roux.

There were two further aspects of Mirror Me that highlighted the innovation within Mars’ practice. The first arose from a glitch. Returning back into the VR body, there was a brief moment where I could see the inner structures of the being’s body. I could see the eyeballs without a skull. The moment was fleeting and something I quickly dismissed while I was participating in the project. Yet, afterwards, I repeatedly returned to that moment. As the project was centred around extrasensory experiences, I questioned whether I should have explored this glitch as a completely new and unique bodily experience.

In a talk in 2021, artist and community organiser Kevin Gotkin offered a generative approach to the glitch. Instead of rushing through glitches and attempting to overcome them, Gotkin asked what would happen if an audience attended to their formal features, recognised their potential to create moments of pause and recalibration, and instead embraced them. (4) Not only did the glitch in Mirror Me offer a truly extrasensory experience but it offered an opportunity to practice patience and open-mindedness, emotions that are often neglected.

In particular, these responses are heavily contested within the field of VR and digital art. VR can be heavily critiqued for its faults, it is judged for its inability to grant perfect and uninterrupted experiences. However, perhaps it is judged too harshly. Very rarely have I ever seen an artwork in its ‘perfect’ viewing conditions. There are always people, time allowances, technical issues, outside noises which interfere with the experience of viewing. Yet, if we can explore the physical sensations of the glitch, the ways in which impatience, annoyance, frustration, manifest in the body, then perhaps these often-neglected emotions can be explored and embraced in our body with the same grace and acceptance as grounding and boundaries in Mirror Me. Perhaps, as Gotkin explores, through accepting the unpredictable and complex mechanics of technology and art, we can understand the complexities of our bodies and selves. Therefore, although unexpected, Mirror Me offers a new way to experience art which not only decentres but critiques the limiting perfectionism within digital art’s reception.

Sophie Mars, Mirror Me, 2021. Photography by Sophie Le Roux.

Moreover, and finally, Mirror Me asks its audience to re-examine not only art’s experience but its language. In conversation with Mars, we discussed how the colloquial term of ‘works’ to identify artworks did not seem fitting. (5) I confessed that the term ‘work’ suggested effort and labour, notions that struggled to fit with such a freeing and invigorating experience.

There is a genealogy of art and performance which actively embraces labour. Mierle Laderman Ukeles 1973 performance Hartford Wash: Washing, Tracks, Maintenance – Outside and Inside spotlighted the labour of low-paid custodial workers in maintaining the pristine of the museum. The artist painstakingly scrubbed at the staircase at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum in Hartford, Connecticut (United States), before buffing the floors of the museum’s interior with diapers. (6) Next, in the choreography and dance performances of pioneering artist Isadora Duncan, the grace and effortless of the balletic tradition was completely overturned. Dancers moved in a way that accentuated the weight and strain of positioning the body in such statuesque poses, positioning her women dancers as icons of a mechanical-like strength, resilience and grounding. (7) Finally, performances by Marina Abramović such as Rhythm 0 (1974) and Rhythm 10 (1973) were based on testing the body’s endurance and “confronting pain, blood, and physical limits of the body”. (8) Therefore, there is a history of conceptualising and framing performance as a form of work or labour.

It seems as though, despite the physical weight and anchoring of the VR technology onto the body, the experience of Mirror Me was not about effort, strain or labour. Within the experience there are no tasks to complete, no obstacles to overcome, simply the pleasure of presence within one’s own body and experiencing the sensations that are evoked or have been ignored in our day to day lives. Even the glitch itself, through Gotkin’s perspective, can be seen as something to surrender to, as opposed to a hindrance to fix. Mirror Me, explains Mars, is not a ‘work’ because it isn’t something to be laboured over. The experience invites us to connect to ourselves and our bodies, to “feel alive and connect and be a channel for ideas” as the artist describes. (9) Mars’ oeuvre enables its participants to connect to ideas that are important socially and within the contemporary moment, creating art that is not ‘artwork’ but experiences. Mirror Me is itself a mirror, reflecting back the opportunities for growth in both contemporary art and ourselves, celebrating the complexities of our bodies and being within the digital age.

References:

Quoted from a conversation with the artist (26.04.2022).

Quoted from a conversation with the artist (12.04.2022).

Quoted from a conversation with the artist (26.04.2022).

Kevin Gotkin at the Accessing Hybrid Events talk, hosted by Caraboo Projects on 15.09.2021.

Quoted from a conversation with the artist (26.04.2022).

Wes Hill, ‘Critics’ Picks’, Artforum <https://www.artforum.com/picks/mierle-laderman-ukeles-48868> [first accessed 26.04.2021].

Carrie J. Preston, ‘The Motor in the Soul: Isadora Duncan and Modernist Performance’, Modernism/Modernity, 12:2 (2005), pp. 273-289 (p. 276-277).

‘Marina Abramovic Biography’, Tate, <https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/marina-abramovic-11790> [first accessed 07.06.2022]. To learn more about Abramović, please see Hans Ulrich Obrist, Marina Abramović (Köln: König, 2010).

Quoted from a conversation with the artist (26.04.2022).

Sophie Mars is a performance artist, dancer, dance movement therapist and body researcher, currently based in Berlin. She is interested in participatory, sensory and immersive work exploring collective energy and idiosyncratic movement as new means of viewing and transforming space both physically and ontologically. Always interrogating the role of the body in today’s digital context, she uses virtual and augmented reality to explore physical and virtual interstices, creating uncanny, dreamlike worlds that are both familiar and utterly surreal. All of her current work and collaborations are linked to her project ‘Mindful Practices for a Future Body - or How to Reprogramme Ourselves’, in which she explores and examines new ways of relating to our bodies and environment.