My Cocoon Tightens - Colours Tease -

Painted Ladies:

An Introduction to the Iconography of Memory, Identity and Metamorphosis in Aziza Shadenova: My Cocoon Tightens - Colours Tease -

By Phoebe Bradley-White, 8 July 2022

Aziza Shadenova, Girls Hovering, 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 30 x 120cm each.

In her first solo exhibition with Ainalaiyn Space, Aziza Shadenova reflects on and reconstructs the memories of her upbringing in Uzbekistan. The exhibition’s title has been lifted from the opening line of American poet Emily Dickinson’s 1896 poem, From the Chrysalis. Dickinson narrates the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly from the perspective of the insect itself:

My Cocoon tightens – Colours tease –

I'm feeling for the Air –

A dim capacity for Wings

Demeans the dress I wear –

A power of butterfly must be –

The Aptitude to fly

Meadows of Majesty implies

And easy Sweeps of Sky –

So I must baffle at the Hint

And cipher at the Sign

And make much blunder, if at last

I take the clue divine – [1]

Dickinson explores the ambivalence of change; while it is embraced and understood as a vital part of life, it is often met with feelings of apprehension and even fear. The poem opens with the uncertainty and discomfort of change. The “cocoon tightens”, evoking feelings of suffocation and entrapment. Yet, “colours tease” which suggests that the cocoon is stretching and perhaps even tearing under the strain of the insect’s metamorphosis. Or, perhaps, the colours of the cocoon are shifting and disorientating the caterpillar, and so teasing its sense of stability and place. Nevertheless, in just five words, Dickinson deftly captures the bewildering nature of change, both tightening and stretching, suffocating and exposing. In an attempt to overcome the claustrophobia and helplessness of its sudden transformation, the caterpillar begins “feeling for the air”. This line in particular constructs a narrative of a creature who is at first threatened by its transformation.

In the second stanza, the caterpillar assesses both the weighty expectations and the liberation that result from growth. In its newly transformed state, the insect will have the “power” to fly. Describing the butterfly’s fluttering as “easy Sweeps” suggests a mastery and agency that compliments Dickinson’s earlier description of the scene as something endowed with “majesty”. Therefore, the semantic field of the second stanza offers a more empowering, and so positive, perspective to change.

The final stanza expresses the insect’s revived determination. No longer helpless, powerless and desperately scrabbling for pockets of air, the caterpillar embraces the imperfection of moving through change. Yes, the caterpillar “must baffle” and “make much blunder” but it will also “cipher”, crafting its own voice and expression. At the climax of its metamorphosis, the butterfly will “take the clue divine”, implying both the active assertion of taking or reclaiming, and the ecstasy and “divin[ity]” of completing such an arduous process.

Therefore, the imagery and symbolic imaginary of the butterfly plays a central part in Shadenova’s exhibition. Yet, the butterfly is not only present in its literal depictions within the artist’s work. The installation of the polyptych Girls Hovering plays with reflections and symmetry. The minimal silhouettes mimic the symmetrical patterns of butterfly wings. In a similar way, the use of bows and flight of darts within the works recall the shape and silhouette of the butterfly.

However, Shadenova’s engagement with a butterfly’s complete metamorphosis can also be detected on a symbolic and biographical level throughout this new body of work. Recalling Dickinson’s narrative, Shadenova explores the experiences and sensations that enabled her own identity and sense of self to transform. The exhibition predominantly features young girls as they play with hula hoops, dance and twirl, and tend to their family. The artist also focuses on her time in Uzbekistan, a period of her life that coincided with her adolescence. The subjects of the exhibition resonate with Dickinson’s caterpillar; they are young, curious and playful as they “baffle”, “cipher”, “make much blunder” and craft their own identities and lives.

Butterfly Girl Drawing, by Aziza Shadenova on the window of Exposed Arts Projects. Photograph courtesy of the author.

The dialogue between Shadenova and Dickinson is epitomised in the line drawing painted directly onto the glass at Exposed Arts Projects. (Please see image above.) The drawing depicts a nude human figure with two long plaits, antenna and wings. Again, the drawing plays with ambiguity, echoing the ambivalence of change: is the figure curling up in discomfort, as though they are recovering from the pain of the tightening cocoon? Or perhaps the figure is crouching and just seconds away from vivaciously soaring into the air with their newly-discovered “Aptitude to fly”? Are the figure’s eyes closed in exhaustion, or are they wide awake with the vigour of rebirth? The figure’s body also feels somewhat androgynous. While the exhibition contemplates formative moments in the lives of girls and women, Shadenova’s window drawing reminds the viewer that transformation is universal and intrinsic.

Throughout histories that span across many times and geographies, both art and the figure of the artist have been heavily intertwined with the narrative of transformative rebirth. German performance artist Joseph Beuys often told the story of how he crashed his warplane due to a blizzard. He was rescued by nomadic people who swathed his body in fat and felt for protection and warmth. Beuys retold this narrative throughout his career in which the act of being cocooned in fats and fibres became emblematic of his transformation and rebirth and enabled him to craft an art practice that promoted non-violence and social awareness. [2] Even artworks themselves offer moments of transformation. Yoko Ono’s Bag Piece from 1964 encouraged visitors to climb into a fabric bag and “to become something totally different”. [3] Ono hoped that the experience would strip the participant of their social identity, allowing them to locate their “spirit or soul” and rejuvenate their sense of self. [4]

Additionally, art history evidences the ways in which the butterfly has been closely connected to the human spirit. With its delicate paper-thin wings, the butterfly’s fragility serves as a reminder of the human body’s own state of continuous precarity. The cocoon and the caterpillar’s transformation into a butterfly have often been seen to symbolise the volatility of life and the ways in which the human subject is incubated and irreversibly changed by moments throughout their life.

For example, in Ancient Greek mythology, the goddess of the soul, Psyche, was conventionally depicted with butterfly wings or in close proximity to a butterfly. In works such as Jacques-Louis David’s Cupid and Psyche (1817), the sleeping goddess is framed overhead by a white butterfly; it’s colour and daintiness capturing the innocence and delicacy of her slumber.

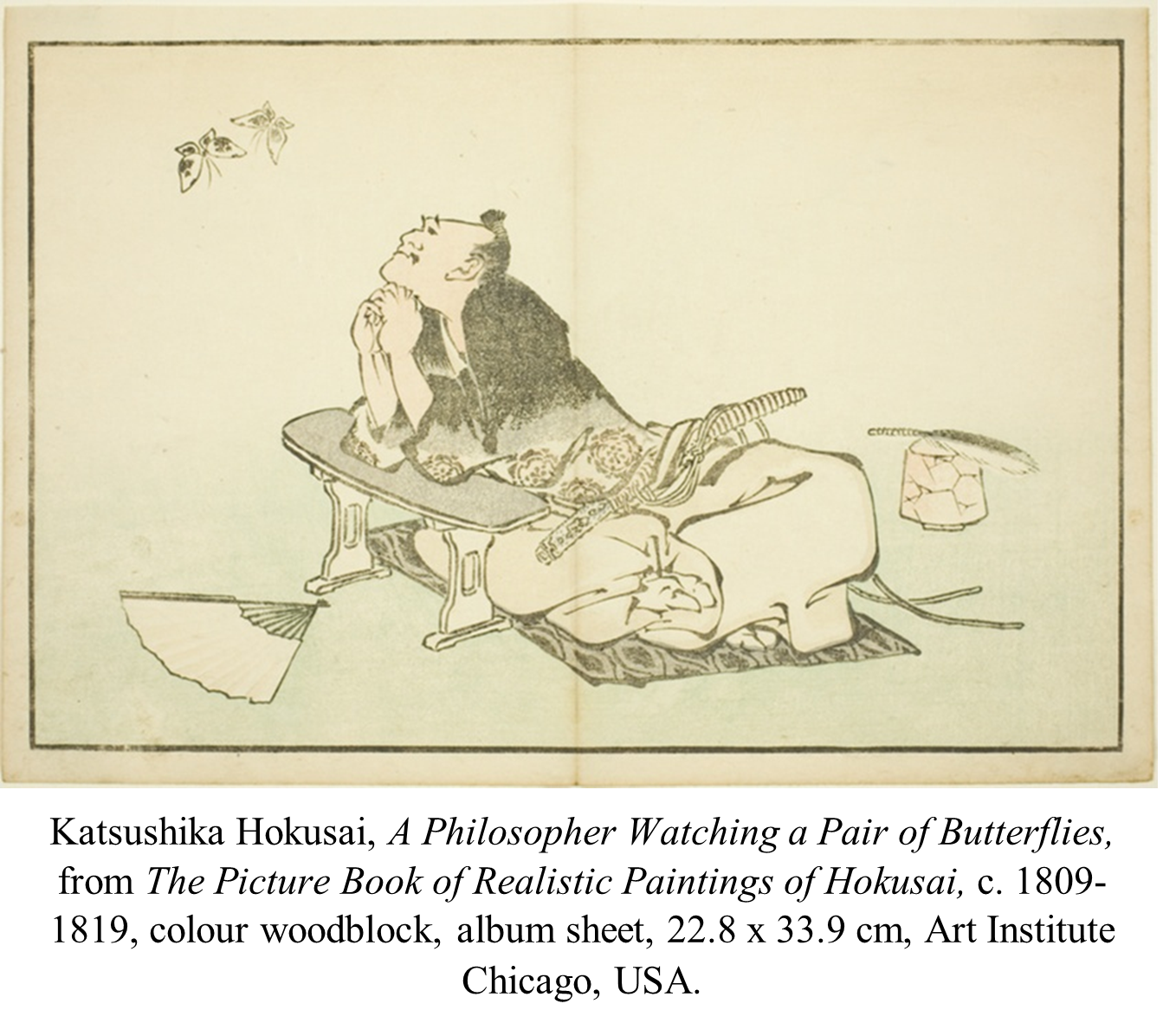

Hokusai’s colour woodblock A Philosopher Watching a Pair of Butterflies (c. 1809-19) also features the butterfly as a symbol for human consciousness. Cradling his head in this hands, Hokusai’s philosopher is lost in quiet observation. He is surrounded by objects associated with lightness and fragility, such as a feather, a fan, and delicate ribbons. Yet, even these objects lie heavily on the ground. It is the only the butterfly, animate with spirit, that can dance in the air. The butterflies prompt the philosopher to contemplate the fragility and fluidity of the human mind and being. Like Psyche, the butterflies flutter just above his head, again conveying the ephemerality of his ruminations.

The connotation of delicacy and ephemerality is also evident in seventeenth-century Dutch still lives, such as Maria van Oosterwijck’s Vanitas met hemelglobe (1668). Here, the Red Admiral butterfly sits on a passage from the Old Testament’s Book of Job which features the lines: “Man born of woman is of few days and full of trouble […] he springs up like a flower and withers away; like a fleeting shadow, he does not endure”. [5] In dialogue with the text, the butterfly symbolises the passing of time, the futility of worldly possessions, and the fleetingness of human life. [6]

Yet, in more contemporary artworks, such as Frida Kahlo’s Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), the butterflies that adorn the artist’s hair signify rebirth. After Kahlo was involved in a bus collision at the age of eighteen, the artist was left with life-long injuries. In her self-portrait, the butterflies epitomise her resurrection after the accident, offering hope and the possibility of metamorphoses. In this way, ephemerality is not seen as a melancholic reminder of the fleetingness of human life, but offers the comfort of transformation and growth. In just these few examples, the butterfly represents beginnings and endings as a continuous cycle of transformation and change, offering a nuanced perspective on the fragility of the human body and its being. It is this imagery and symbolic imaginary that Shadenova makes reference to throughout this exhibition.

In My Cocoon Tightens – Colours Tease –, the inclusion of the butterfly within the imagery and installation of the works offers insight into the artist’s understanding of the human condition and memory. Shadenova’s Painted Ladies – referring to both the subjects of the exhibition and the butterflies that epitomise transformation and symmetry – offer glimpses into the artist’s personal past whilst simultaneously restaging memories that will resonate with a wider audience. The works predominantly feature young girls, who much like the caterpillar, are in the process of growth and transformation; their lives punctuated with formative moments that will shape who they become as women. In dialogue with Dickinson’s sensorial description of the cocoon tightening alongside light and colours shifting, Shadenova depicts a multi-sensory dimension to memory. The mother’s tender braiding of the daughter’s hair; the smell of freshly-brewed tea shared amongst family; the tart taste of a pomegranate picked from the garden: these are the moments that make us and the experiences that possess the power to influence who we become.

Such an embodied understanding of memory recalls the writing of French novelist Marcel Proust. In his novel, In Remembrance of Things Past, (1913) Proust recalls a cold winter’s day. Unusually for the writer, he accepts his mother’s offer to make him tea. He describes the unexpectantly remarkable experience of eating a Madeleine cake which accompanies his tea, as he details:

I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate, a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory--this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was myself. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, accidental, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I was conscious that it was connected with the taste of tea and cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could not, indeed, be of the same nature as theirs. Whence did it come? What did it signify? How could I seize upon and define it? [7]

Here, memories are involuntarily and unexpectantly stirred by long forgotten scents, tastes and textures. When Proust exclaims “the essence was not in me, it was myself” and later states “the object of my quest, the truth, lies not in the cup but in myself”, he describes memories not as something lying dormant within the body or mind, but as the very material of self. [8] Both Proust and Shadenova’s investigations into memory serve to remind the audience that the limits of ourselves are perhaps broader than once thought. The body stores memories and so, the objects of our past live on within an embodied archive. Yet, these objects also store and prompt memory, also making them involuntary and unexpected archives of the body and being. This line of thinking invites the audience to think of identity and subjectivity as both beyond the physical limits of, and yet deeply enrooted in, the phenomenology of the body. It is as though, through memory, we are both deeply embodied yet vastly expansive.

Shadenova explores the rituals, objects and memories from her upbringing in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. For example, Quilt/Korpe is formed of sixty panels, each decorated with the artist’s memories, dreams and reveries. Its name derives from a traditional quilt in Kazakhstan and its grided composition recalls this quilt and the geometric tiles of Uzbek architecture. Its imagery includes camels, pomegranates, Uzbek buildings and ornamental motifs that recall the visual culture of her childhood years. Again, Shadenova does not only recreate memories from her mind’s eye. Quilt/Korpe interweaves the visual and embodied nature of memory by celebrating the overall security, sense of kinship and experience of belonging that accompanies holding and using the korpe. Another important motif that runs throughout the exhibition is the eye, a homage to Central Asia’s shamanic history. Also, the recurring image of plaited hair is deeply connected to the women in the artist’s family who would have braided their hair to commence hard work and labour. Her reference to the braid celebrates women’s resilience and strength, and the integral part these women played in the artist’s upbringing.

Aziza Shadenova, Quilt/Korpe, 2021, oil on canvas boards, 200 x 120cm, 20 x 20cm each.

Yet, the exhibition’s connections to western literature, such as Dickinson and Proust, celebrate Shadenova’s own evolving identity. The dialogue between French and American literary responses to memory and identity and the artist’s memories of Uzbek traditions and material culture highlights the blended identity of the artist herself. Shadenova celebrates the ways in which Uzbek and Euro-American cultures have shaped her experiences and identities. Artworks such as Waterlilies, made from interwoven strips of previous canvas works, allude to the landscapes of the artist’s childhood whilst also recalling imagery such as Claude Monet’s paintings of water-lilies. This work therefore physically embodies Shadenova’s identity as an interwoven tapestry of experiences from Central Asian and Euro-American cultures.

In works such as Quilt/Korpe and within the entire installation, Shadenova plays with tessellation and symmetry. Again, this composition alludes to the forms and ornamentation of Uzbek architecture, yet it also holds further significance in relation to themes of memory and identity. French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan writes of the ‘mirror stage’ as a formative moment in an infant’s life. Looking in the mirror and connecting the reflected image to their own body, the infant’s recognition within the mirror serves the purpose of “identification”. [9] When the subject “assumes an image”, they begin to understand themselves as a unique and distinct identity. [10] Additionally, French philosopher Merleau-Ponty notes the importance of the mirror for allowing the subject to comprehend its body and self in a way that cannot be achieved through interoceptive embodiment or proprioception. The subject can only truly understand themselves as a spectated subject, a person perceived by others, when gazing into the mirror. [11] Therefore, the mirror reflects both affirming and alienating comprehensions of self: on the one hand, it reinforces the subject’s sense of self, and on the other hand, it spotlights an identity that the subject cannot fully control, that of the other looking at them. By staging the exhibition in the mirrored room on the ground floor of Exposed Arts Projects, Shadenova alludes to the history of the mirror as the locus of identity, inviting her audience to consider the memories and processes that assert and estrange one’s subjectivity.

Aziza Shadenova, Water lilies, 2022, oil on woven canvas, 80 x 130cm.

The bilateral symmetry of works such as Girls Hovering creates an atmosphere that feels more familiar than unnerving. This series depicts the silhouettes of the young girls that attend to the women of the family. If the women in Dastarkhān are the grandmothers, mothers and aunts that sit around the table, these narrow rectangular paintings depict the young girls of the family that flutter around them like butterflies, constantly refilling their empty tea cups. In symmetry there is harmony. There is a comforting familiarity and a reassuring effect in the balance of a symmetrical composition. Within the mirrored installation of Girls Hovering, the silhouettes of the young girls become the wings of butterflies. Like Dickinson’s caterpillar transforming within the chrysalis, Shadenova stages the transformation of the young girls within their familial experiences. Here, the artist articulates memories of cultural traditions and family rituals as affirming for a young identity and central to one’s sense of belonging.

Yet in other examples, the exhibition’s staging dramatises how memories cannot always be trusted. For example, in Dastarkhān, the hands holding cups of tea and so people, are multiplied within the endless mirrored reflections. This installation recalls the recollection of memories and the ways in which they often become tainted or made strange after long stretches of time. There is often doubt regarding exactly how many people were there, who in particular attended, and whether the reunion was joyfully or overwhelmingly busy. These fragments of memory become warped, positioning the mirror as something similar to the passage of time on our own recollections.

Aziza Shadenova, Dastarkhān, 2022, oil on canvas, 70 x 80 cm.

Therefore, like the eyespots on the wings of a butterfly – both an object of beauty and a strategy for protection – the bilateral symmetry of Shadenova’s painted memories highlights the duality of memory. Stressful memories become humorous; fond memories are intensified by ‘rose-tinted glasses’; and loving memories are tainted by pain. In a similar way, My Cocoon Tightens – Colours Tease – exemplifies the polarity of the past, and how memories themselves can transform and become beautiful in the chrysalis of the mind. Shadenova explores how the past can be both a source of comfort and discomfort, welcoming ambivalence and contradiction within ourselves. If, as Proust suggests, “the past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) which we do not suspect”, then, as the audience moves through the exhibition, they may find their own memories are unexpectantly stirred. [12] Even if the setting or narrative of the painting is not explicitly obvious, the audience is invited to navigate their immediate bodily response to the works and their involuntary mental associations. Therefore, My Cocoon Tightens – Colours Tease not only welcomes the audience into the artist’s past and identity but may welcome the audience back to themselves.

References:

Emily Dickinson, ‘Poem 6: From the Chrysalis’, 1896.

Walker Art Gallery, ‘Joseph Beuys’, Walker Art Gallery, (date unknown) <https://walkerart.org/collections/artists/joseph-beuys> [accessed 30 May 2022].

Yoko Ono quoted in Museum of Modern Art, ‘Yoko Ono: One Woman Show: 1960-1971’, Museum of Modern Art, (date unknown) <https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/15/374> [accessed 2 June 2022].

Ibid.

Book of Job 14:1-2 quoted in Matthew Wilson, ‘Butterflies: The Ultimate Icon of our Fragility’, BBC Culture (16 September 2021) <https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210915-butterflies-the-ultimate-icon-of-our-fragility> [accessed 17 May 2022].

These three works were grouped together in Wilson’s article. (Please see reference above.) Their interpretations are the author’s own.

Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff (London: Chatto & Windus, 1922), p. 52.

Proust, pp. 52-53.

Jacques Lacan, ‘The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience’, in Écrits, The First Complete Edition in English, trans. Bruce Fink (New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006), p. 95.

Lacan, p. 95.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘The Child’s Relations with Others,’ in The Primacy of Perception (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964), pp. 96–155.

Proust, p. 52.